Your Cart is Empty

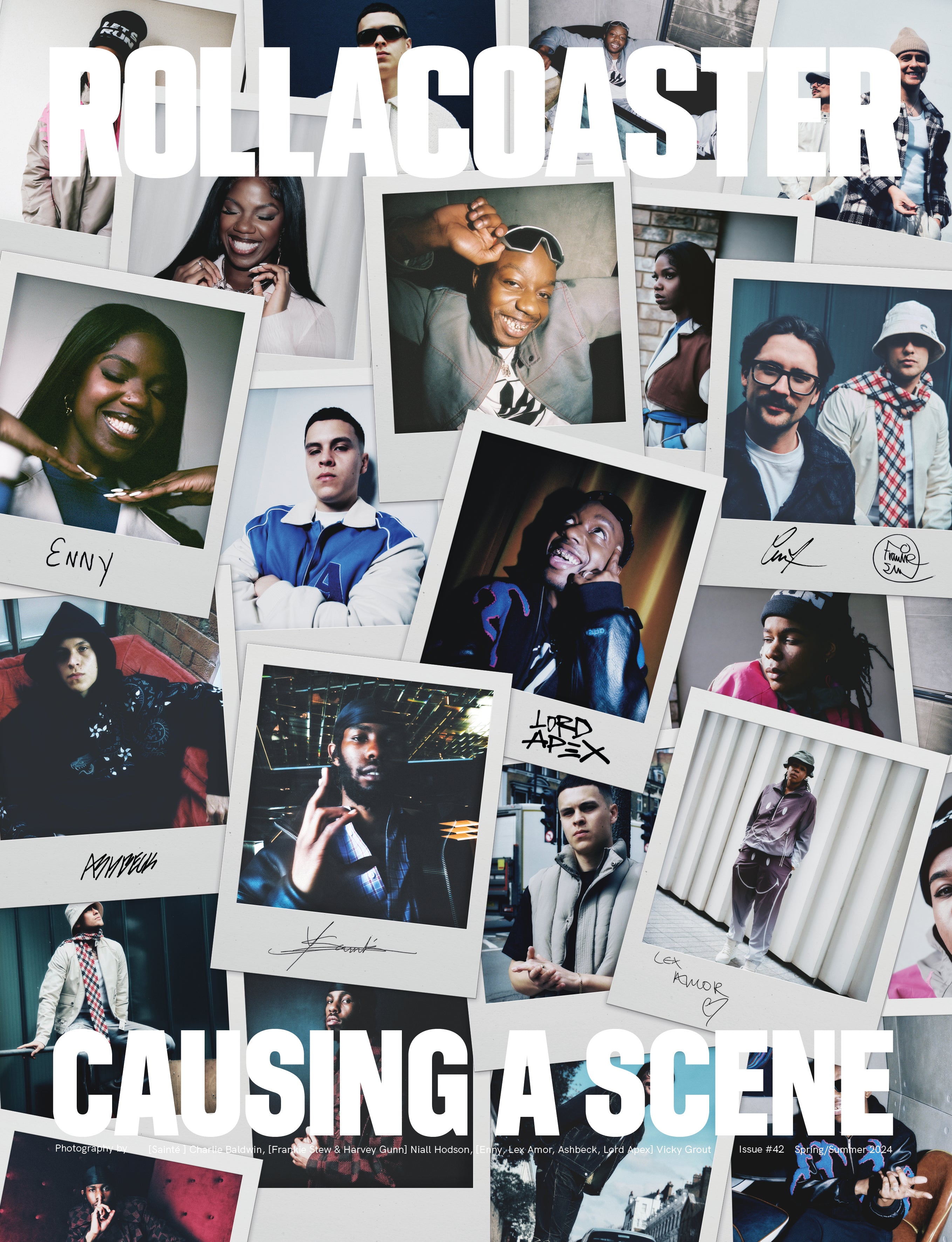

Perennial West London rapper Lord Apex has entered the next phase of his career. Last year dropping one of the UK scene's best albums with his debut full-length, The Good Fight, I meet the wise, witty and wary 27-year-old underground favourite in good form, hungrier than ever.

“This Wetherspoons is lit bro, I’m not gonna lie!” Exclaims a merry Lord Apex. We’re cosied up in a far corner of the Tottenham Court Road branch of the popular pub chain, enjoying a light Friday evening tipple. He advises me to steer clear of the nachos though—and given the overwhelming sense of integrity that he brings to our conversation, I’m mindful to take his word for it.

I find the UK underground rap inaugurator flying high following the release of last November’s debut album, The Good Fight, an instant scene classic. Apex is off on a UK and European escapade throughout April, touring double-figure dates including a climactic homecoming show at KOKO on 20th April (420 to those who celebrate). “For someone that doesn't really do a lot of promo, I'm really happy with the amount that we've done for this album,” he says between gulps of his lager. “I just want to continue to keep that energy going.”

Apex is a notoriously enigmatic figure, assiduously idiopathic, a trailblazer within the alt-rap zeitgeist. Despite being only 27 years old, he considers himself “15 years deep” into his musical tenure, with a discography unparagoned amongst his cohort in quality and quantity alike. From his infamous trio of “Smoke Sessions” mixtapes (he tells me of a fourth volume in the works) to collaborative projects with revered producers like Cookin Soul and V Don, there is immaculate depth, diversity and character to the West London native’s layered catalogue. Yet, with his acclaim spreading like wildfire with the recent unveiling of a long-awaited full-length record, Apex’s odyssey has barely begun.

“It's been a journey and a half,” he sighs reminiscently. “I think it's always been made to look like I'm a bit newer than I would consider myself. People look at you from the point where you start to pick up traction as opposed to where you genuinely start from. I started making music in 2009 so that's 15 years, you know, but when I dropped The Good Fight, it felt like I was just getting started. For a long time, I think it was more something that I was naturally gifted with, but it took time for me to take it truly seriously and do this to 100% of my capability, which is something I'm striving more towards now.”

Like many breakout rappers, Apex began his rise attached to a collective that share a wider mission of community spirit and artistic unison. Elevation Meditation, of which he is a founding member and is still interlinked, is known as one of the most impactful alternative rap collectives to emerge in the UK. Originally known as Shinobi Boys before settling into the Elevation Mediation handle, AP reminiscences of the group forming in West Ealing Park, an area that the rapper has currently found himself situated in once again, a “full circle” moment for him.

The respective members of EM have sought success in their own right and found each other through natural occurrence. Their coalescence “all happened so organically.” Louis Culture, who Apex initially met through a mutual friend, has transitioned into a pillar of electro-tinged experimental alternative rap, and recently shared a sprawling new solo body of work, “I Can’t Wait To See U Again”. Apex’s friendship with Culture brought p-rallel into his artistic orbit. The producer and DJ has gone on to establish himself in the upper tier of UK beat-making, known for the breadth of his sonic vision and collaborations with a series of UK favourites, from Rachel Chinouriri to Greentea Peng. p-rallel was school friends with Finn Foxell, whose genre-bending sound has cocooned from glitchy grime-tinged rap to punk-infused indie bangers. Foxell brought in the fifth and final member, Xav.

EM, alongside contemporary collectives like Nine8 and House of Pharaohs, has redefined the boundaries of what alternative-leaning rap groups can achieve in the UK climate. Offering a support system and a launchpad to cement their status within the scene, although EM haven’t released much in the last few years they are still very much syncopated in ideology and kinsmanship, popping up with the odd group show and consistently backing each other’s musical causes. “We bonded because we had the same love for the music we were into. We all fell into that alternative category but everybody was so beautiful in their own right. The range varies, but we weren’t trying to be alternative music. This is just what we're naturally into, and as much as everybody [has] their own style, we can come together and have a common sound.”

In the earlier years of his career, Apex feasted with a substantial portion of the underground’s banquet, including many of the scene’s forefathers, sewing his name into the tapestry of the movement’s legacy. Blah Records, the conception of North West England’s cult heroes Lee Scott and Salar, played a significant role in Apex building momentum and refining its nuance. The label has long been at the core of idiosyncratic British hip-hop, nurturing some of the country’s finest avant-garde spitters. They, more than anyone in UK rap, holster a “fuck the industry” ethos, a philosophy that Apex respects. “As much as they put out a lot of music and they've got a lot of artists under [their label] now, I don't think [mainstream success] is truly what they're after. I think they're comfortable in their own lane. I’ve got a lot of love for them and I definitely would say they are pioneers of this whole UK shit.”

The alt-rap scene, which AP has been at the heart of throughout his career, has risen to unfounded heights in the last few years, traversing from the depths of sticky 200-capacity basements to London’s biggest venues. Its increased establishment within the wider framework of UK rap is celebrated by Apex, but he is simultaneously wary of shackling himself to its populism. “There's a lot coming out, a lot more people unafraid to just rap and not be on some image thing,” he observes. “I’m seeing a lot more unity in the scene. At the same time, I’m very much in my Lil Wayne bag of being very removed. Unless one of my homies is putting me onto it, I’m not really hearing what's coming out, and I avoid sounding like anyone else. I get basic comparisons all the time, and comparisons are the thief of joy. For the most part, anybody you compare me with, there's no competition with nothing, bro.”

One manner in which Apex divaricates from his counterparts is in his listening demographic. “I had a US fanbase before a UK fanbase,” he says, with his States-side love affair mirrored within the musical taste and social climate of his youth. He grew up intertwined with elements of US culture, with “a lot of homies from New York, a lot of homies from Florida,” and listening to, in majority, American artists. “I would never shit on the UK because it's where I'm from and it's what I love, but I have always acknowledged that rap started [in the States]. If rap started in Pakistan, guess what I'd be listening to? If it started in the UK, I'd be listening to UK rap, but it didn’t. So as a person who is very big on history and very OCD, I’m into chronological order. I went to where rap started.”

An inherent student of the game, Apex’s study of the seminal artists of the rap genre – Rakim, Tupac and Slick Rick to name a few – have deeply impacted his approach to the craft. From his effortless flow and nonchalant delivery to a dexterous tonality and storytelling-driven lyrical nous, the West Londoner brings culture, charisma and colour to every beat he touches—most of which are devised by producers outside of his home nation. US rap fans often struggle with UK rap in its actuality, whether it be the sonic palettes or the sharper aggression of many of Britain’s MCs. Apex is an anomaly to the theory; his empathy towards American sonics allows him to spread his sound across multiple continents, whilst still feeling grounded within his Metropolitan identity. From stoner rap to boom bap, trap to soul-tinged lo-fi, Apex’s hip-hop circumference is daring and multi-dimensional.

“I'm always looking to be different,” he affirms. “I don't want to make a song and it sounds like some UK shit. But at that time, I felt like I had to prove to the people over here who were doubting that I could be on that [UK] shit. I could rap like that too, it's just not my personal preference. It’s so tiring to me because everybody in the UK was doing it the same [he demonstrates a vocal flow synonymous to UK rap], and then all the subject matter is the same: we all trapping, we're all not lacking, we've all got one foot in and one foot out, and my man's not here no more because he spoke on the net and he got poked up. It’s all about being dangerous and all about shock factor but to me it's boring bro—I’d rather rap about fucking Colgate.”

For Apex, when the ball dropped and the time came for a sought-after sonic statement, he knew that his debut album had to be a body of work as near perfect as he could ascertain. The LP’s tracklist is meticulously crafted, from the beat selections to the angular thematics. Collaborators are significant to the album, as he said on 2021’s “Smoke Sessions 3” cut “Speak For Yourself”: “Mostly I like to work alone but I know features can help.” Carefully selecting his album’s cast, he enlists mostly US mainstays, such as legendary producers Madlib and DJ Khalil and boundary-pushing rappers Mavi, BONES and, perhaps most impressively considering the ardency of his critical acclaim, Freddie Gibbs, whom Apex has previously supported on tour.

Most of all though, The Good Fight is about Apex flaunting his own thoughtfulness, an ambition to be free in his art, and the peerless perpetuity of his imagination. “That first album is pivotal because you're only ever gonna be that hungry once. I wanted to make an album that best represented who I was as a person but then also wanted to show that I can be more vulnerable in certain songs. I wear my heart on my sleeve so I try to just use that in confidence; music's a therapy for me, so anything I speak on is never for shock value or any bullshit, it's really just me speaking on what I've gone through. I'm not really thinking about any outside entities.”

Parallel to a flourishing wave but never caught up in its waters, Apex swims in prosperity alongside his contemporaries, but he needs no aid in floating. In fact, he dives deeper into individuality than those around him who stick to more shallow shores. “You have to create your own industry,” he says. “I try to play it in a way where I make people come to me. I wanna work with people and I'm open to be with everybody but I can't conform and be part of every part of the industry. If you create an industry around yourself, that industry can never fail you.”

Lord Apex is undoubtedly one of the most iconic and important players in UK underground rap’s last decade. Beneath a resilient and playful posterior lies a romantic, a deep-feeler and a philosopher. He’s grateful for his journey, learned of his past and directive in his future. “I used to have very high aspirations for things,” the West London rapper tells me as we prepare to leave the hectic bliss of the last few hours and head out into the windy central London dusk. “But then you get things and you're like, ’these are not fulfilling.’ The love, the memories you make with people, the people you meet along the way on the journey, the places you go to, those are all fulfilling to me. People message me like, ‘Yo, this song got me through this.’ And they don't even know that their message got me through that. That's the shit that means everything to me, man.”

Photography by @vickygrout

Styling by himself

Interview and words by @tibbitsben

Editorial Director @charlottejmorton

Editor-in-Chief @ellaxwest

Creative Director @jeffreythomson

Art Director @harry_conor

Assistant Art Director @beth1owri

Production Director @bencrankbencrank

Production Assistant Lola Randall

Grooming by @courtney_reece_scott

Special thanks to @chateaudenmark